Luca Lombroso, AMPRO Meteorologist and Foreste per Semper odv volunteer

The Karen Mogensen reserve and surrounding areas, such as the Rio Blanco valley, were hit by a violent storm on Monday 22 July 2024. Thanks to the data collected by the meteorological station located at the “Italia Costa Rica” Meteoclimatic and Biological Station, we analyze what happened from a synoptic weather point of view and any links with climate change.

Weather data and webcam images

Fortunately, on the day of the event, both the weather station and the webcam were functioning, providing valuable data displayed in real time on the website www.biometeo.org and as an archive to the server and database of the Geophysical Observatory of the Engineering Department ” Enzo Ferrari”, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia.

As for the webcam, the timelapse shows a rapid development of cumulus clouds since the morning, with a cumulonimbus already present in the late morning but which did not directly hit the Karen Mogensen reserve. In the afternoon the cumulus clouds also tend to thicken on the reserve, with dark and threatening clouds from which, from around 4pm, rain drops so large that they are visible from the webcam begin to appear. Lightning and flashes do not appear to be visible. The heavy downpour continues until dusk.

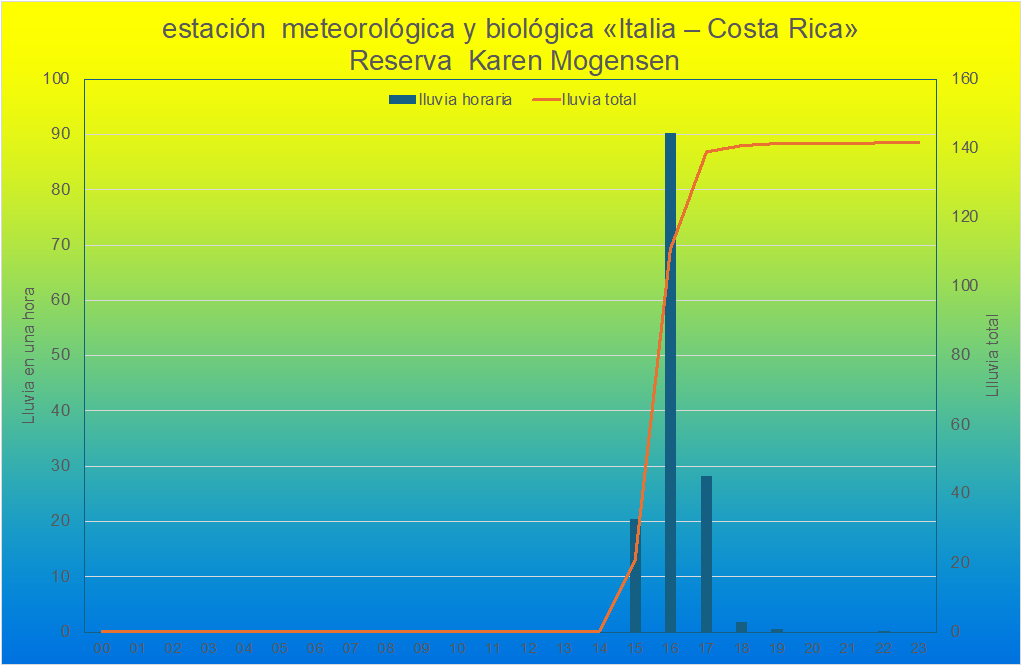

As for the weather data, the rain gauge records the first weak rainfall at 3.40pm local time, with rapid intensification and constantly very heavy rain until 5.15pm, followed by residual weak rainfall. The maximum intensity was recorded at 4.40pm, with 9.4 mm measured in 5 minutes, while the instantaneous peak of rainfall intensity was found at 5.10pm with 188.8 mm/hour.

Overall, 141.6 mm fell during the day, the majority, 138.8 mm, concentrated in the 3 hours from 3pm to 6pm, with an hourly maximum of 90.2mm between 4pm and 5pm.

Nothing significant emerges from the temperature trend, after a maximum of 29.5°C at 12.35 during the storm, 28°C was found at the beginning of the rainfall with a drop to 22-23°C in the most intense phases.

The trend in atmospheric pressure is interesting, with an initial increase even during rainfall, followed by a drop of around 2 hPa at the end of the phenomenon, around 7pm and a subsequent new increase, with hints of a classic “pressure tooth” in the trend barometric.

The weather situation

The National Meteorological Institute of Costa Rica in the warning issued at 1:45 pm on July 22, 2024 indicated that “The proximity of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) to the national territory is bringing a significant contribution of humidity and instability. This is causing cloud formation and, consequently, episodes of localized heavy rain and thunderstorms in the afternoon, which may persist into the early evening.”

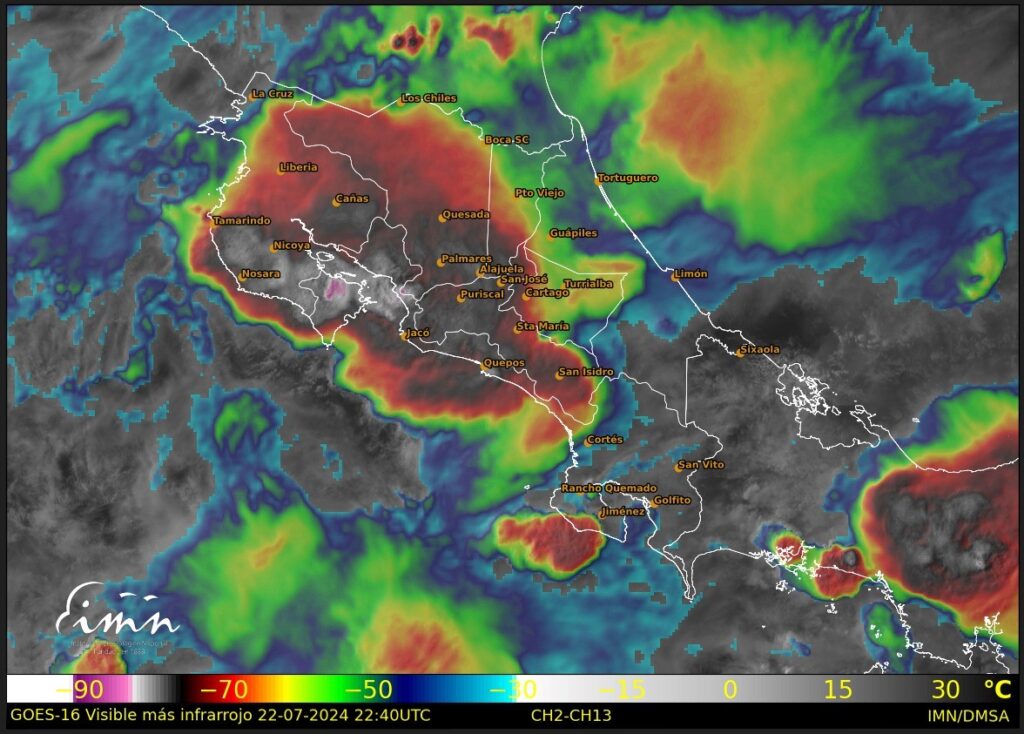

This is confirmed in the maps, the ITCZ passed right over Costa Rica, and at the time of the event the satellite images showed a large accumulation of convective clouds, perhaps even with MCC characteristics. An MCC (Mesoscale Convective Complex) is a large system of organized thunderstorms that covers an area of at least 100,000 km² and lasts at least 6 hours. Characterized by a circular or elliptical shape, an MCC develops in the afternoon, reaches maximum development during the night and dissipates in the morning. It produces heavy rainfall, strong winds, hail and lightning, and can cause local flooding. It is common in the Great Plains of the United States during the summer, but can occur anywhere, including the tropics, if weather conditions are favorable.

The satellite image then analyzed in depth indicates a cloud top temperature of 197°K (-76°C) in the area, a notable value which supposedly leaves clouds 15-16,000 meters high.

Historical comparison of rainfall

We have almost continuous data since the beginning of 2017, a short period for climatology but these 8 years already provide us with important information.

This rainfall is, over 24 hours, the second most abundant, surpassed by the equally alluvial event of 3-5 October 2018, in which 422.6 mm fell in the three days, with a peak of 244.4 mm on 4 October 2018. instead the most abundant for the month of July, the previous maximum was on 3 July 2020 with 105.0 mm.

However, the hourly rainfall of 90.2 mm and the three-hourly rainfall of 138.8 mm were absolute records since the beginning of our measurements.

Link with climate change

The attribution of heavy rainfall events to climate change is a complex topic that requires in-depth analysis with models.

We limit ourselves here to some considerations without drawing definitive conclusions: certainly July, although sometimes characterized by the “veranillo”, the short stable period in the rainy season, is still a very rainy month, with an average in the Karen Mogensen area of 390 mm calculated on the “renalises”. It is therefore reasonable to expect very intense rainfall, as occurred in the aforementioned July 2020 and also partly in 2017.

From the point of view of the El Niño or La Niña cycles, we are currently in an approximately neutral phase, El Niño has ended but La Niña has not yet taken over, so these cycles cannot have influenced the observed phenomenon.

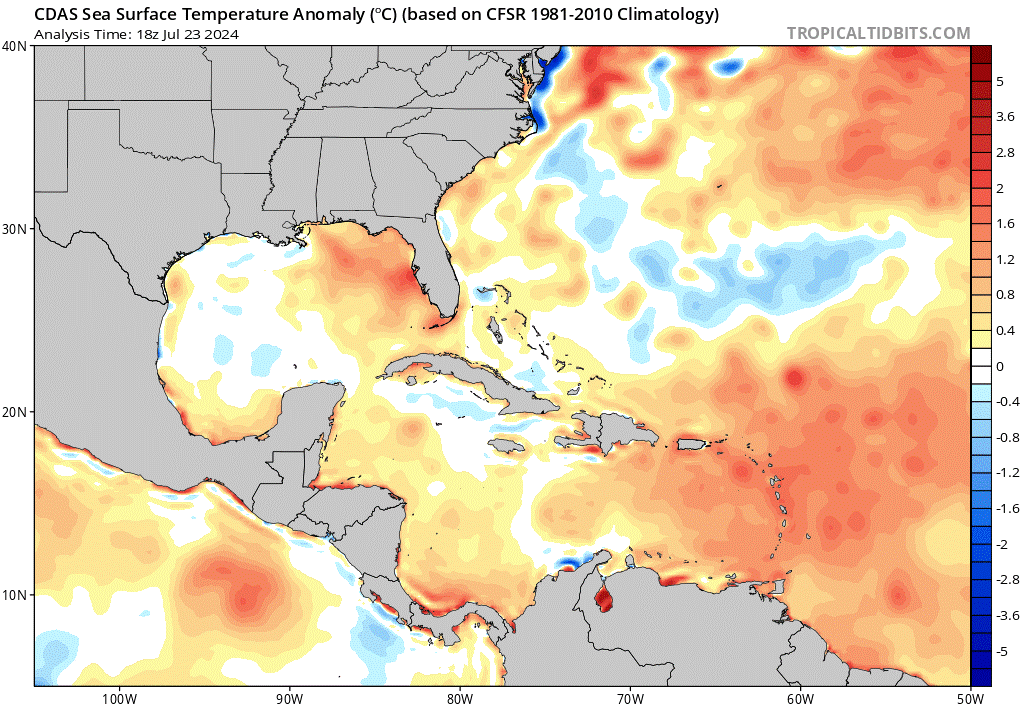

Looking at sea temperatures in detail, a slight negative anomaly is observed in the Pacific Ocean surrounding the Nicoya Peninsula, while the Caribbean Sea is significantly warmer than average.

Generally, in a warmer climate like the current one, more “precipitable water” is available; each degree of increase in temperature increases the humidity load that the atmosphere can contain by 7%.

In summary, this event could still be an intense event typical of the rainy season, but it is certainly possible that climate change contributed to making it more extreme.

Prediction and prevention of these phenomena

The strategies for mitigating and reducing greenhouse gases, which are essential, will only take effect in the future, and can no longer avoid extreme events, at most if implemented (but the world is significantly behind in the application of the Paris Agreement on climate ) can prevent these events from degenerating further and becoming unmanageable.

These events, in general, are now part of the rest of a “new normality”: similar and even more abundant rainfall also occurred in Emilia Romagna on 23-25 June 2024 with floods and local floods in the Modena area, and on 16-17 May 2023 in Romagna with the dramatic flood.

Adaptation is therefore also necessary, which is not and must not be an alternative to mitigation. Costa Rica already has a national climate change adaptation plan.

At a local and community level, however, the Costa Rica Italia Station, with the action of the Foreste per sempre association, can act as a spokesperson for training the population and tourists on the rules of behavior in the event of these events. Already during a past edition of the “field school” a seminar “Beware of the Weather” was held with UNIMORE students, a course aimed precisely at self-defence from extreme events.

Another topic to be explored further is that of early weather warnings, to warn the population in advance. However, this topic is also more complex operationally.

Weather station problems

Finally, some thoughts on the weather station. For several weeks the weather station had been experiencing hardware problems with the sensor suite, with loss of signal and data. Fortunately, thanks to the coordination with Alex Bolaños, the problem of changing the internal battery of the sensors was at least temporarily solved, and on the day of the event the data was complete and of good quality.

Unfortunately, since July 24th we have been experiencing technical problems again, which suggests major problems with the transmission board, which will probably have to be replaced.

The intervention requires both spare parts to be purchased and adequate technical intervention, so we will try to evaluate the best solution to give continuity to this important data.

Already today, however, we can say that the weather station is proving to be a valuable instrument for observation, scientific research and also information for the population and tourists.